Since I began this career, I have been interested in exploring the best ways to study Chinese medicine.

When I first started school, the sheer volume of information I had to absorb was overwhelming! However, the amount of information wasn’t the only problem. There was also an astonishing diversity of TYPES of information. Chinese language materials, conventional anatomy and physiology, artistic expressions of complex concepts, qigong movements, pulse sensations, books and PDFs – and that’s a tiny portion. To study Chinese medicine well, it seemed, I’d need to deal with all this input, not just for tests, but for supporting my future clinical reasoning.

I was seeking an ideal method for “knowledge management.”

Knowledge management refers to the collection, generation, consumption, manipulation, storage and retrieval of any kind of information. When you hear the term online, it’s almost exclusively referring to digitized information. But, it can refer to books, written notes and other analog forms of information. Over the years, I’ve experimented with countless hardware, software, and analog knowledge management tools all intended to improve my study of Chinese medicine.

The knowledge management tools I’ve talked about most here are, in some ways, just a digital version of an analog file cabinet with folders.

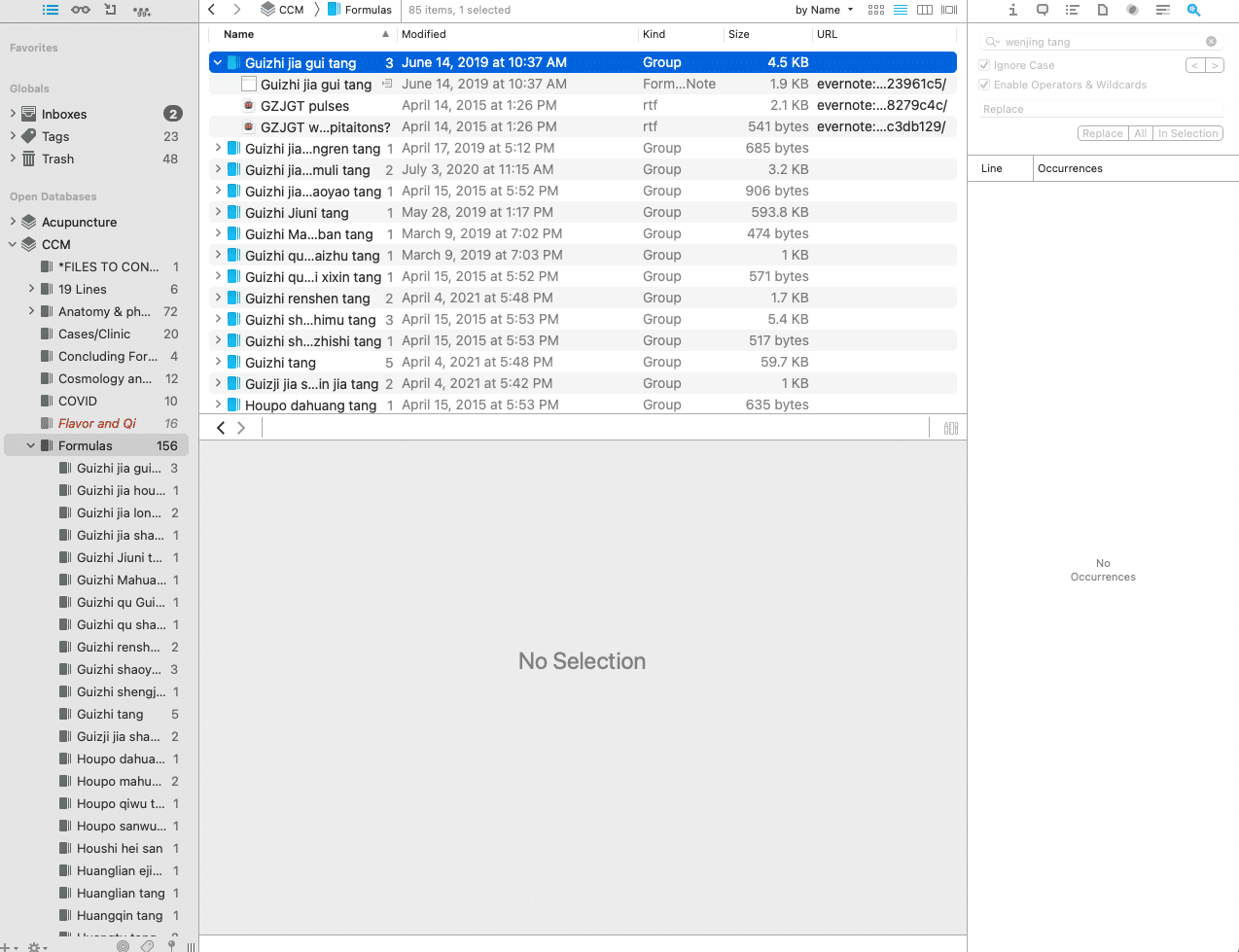

Evernote and Devonthink are the two I’ve used most, and I still use Devonthink for some purposes now. These “database” applications are an upgrade over paper because you can add all kinds of forms of information from website snapshots to videos to handwritten notes, really anything you can digitize. They also allow you to access the information from pretty much anywhere, and manipulate it wherever you are.

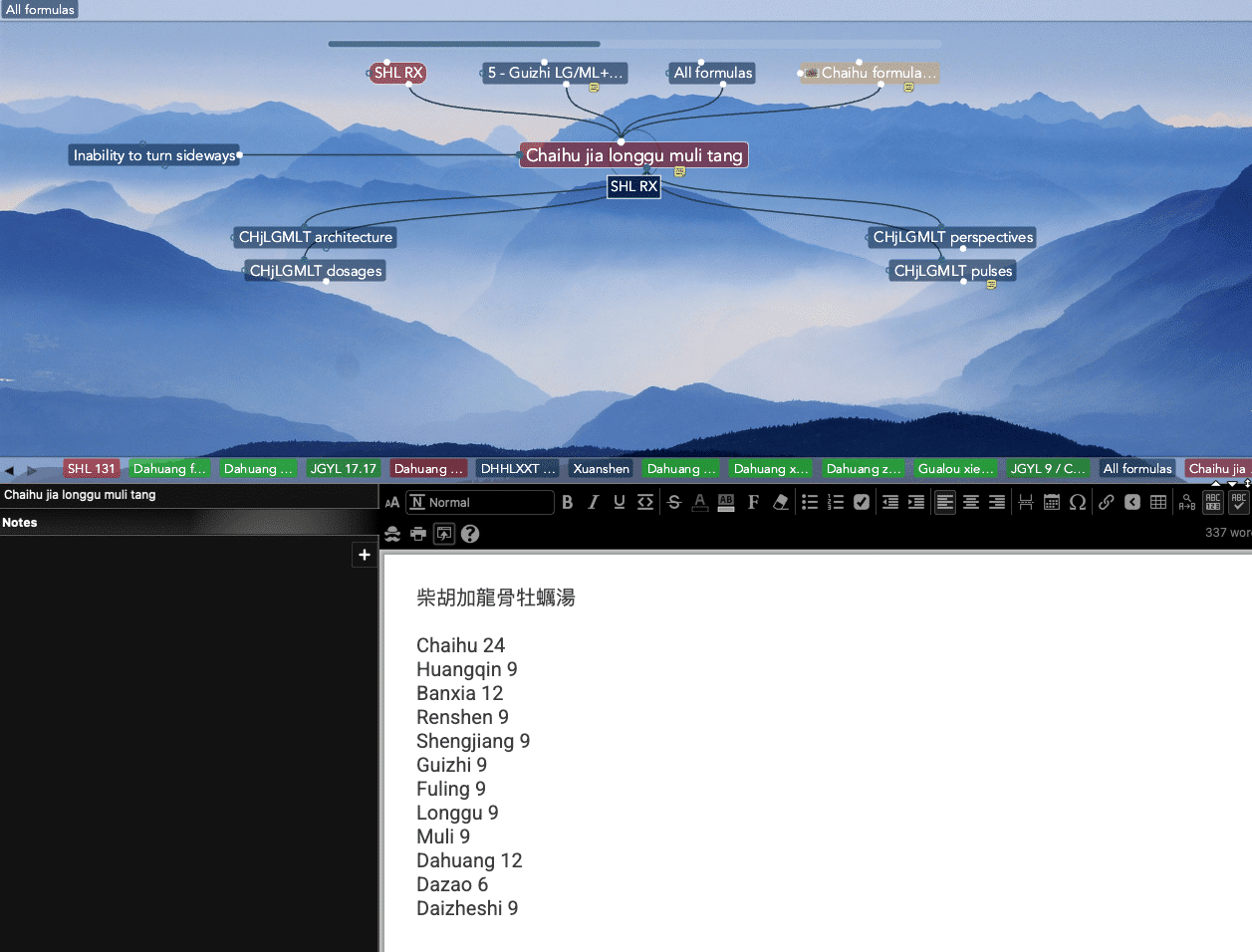

I’ve also been a major fan of digital mindmapping. There are some stages of a project or thought process that seem to be enhanced by the flow that emerges from the mindmapping process. My very favorite mindmapping tool, which I use for both business and study purposes, is TheBrain. It represents a big upgrade over typical mindmapping software because of its multi-dimensionality. Any piece of information can be interconnected in many ways to other pieces of information. That focus on interconnectedness, actually, was what pushed me into my latest hunt for my ideal knowledge management system.

Over time, I’ve discovered that the “file cabinet” model, which is also present to some extent in TheBrain, is the foundation of my problem.

Why? Because INFORMATION STORAGE is not the problem I’m actually trying to solve. I’m trying to solve the problem of knowledge management. The distinction is important. Storage is static. Management is active. That activity, actually working with and coming into relationship with the information you have collected is the core of knowledge building. And that’s what I truly need as I study Chinese medicine.

During our pandemic shutdown, I engaged in a new hunt for a knowledge management system. I also hoped to solve many of the nagging problems I encountered in all of the systems I’ve tested so far.

I determined I wanted my new knowledge management system to have the following features:

- It leaves my information as compatible with as many other systems as possible. I don’t want to be locked in, or to have to take too many steps if something else might work better.

- It allows me to backup my data in multiple ways, including analog copies of my most important information (like pulses and formula guidance from my lineage)

- It gives me multiple ways to visualize my data. Sometimes I find working with outlines to be best, sometimes I like to have a more narrative approach, and I like different timelines and mind maps for certain kinds of work.

- The system can deal with multiple file formats. While my most important information is in PDFs and text files, there are several multi-media files, website URLs and other formats of information that I need to organize and retrieve.

- It is accessible on every device I use. That means iPhone, iPad and desktop/laptop. It’s ideal, too if there is some type of web interface in case I cannot access my devices.

- It’s fun to use. This is a weird one. I am very sensitive to user interface (UI) design. If it’s ugly or hard to use, I am out. This is a very subjective aspect of evaluating software. Your mileage may vary.

Once I felt clear about what I needed, I started the hunt in earnest.

It was during this hunt that I discovered the term “knowledge management” as such. In looking into more about it, I ran across a FREE app still in beta development called Obsidian. It is often mentioned in the same articles with a similar app called Roam research. I feel lucky to have been searching for a solution during an exciting time in the development of knowledge management apps!

Obsidian is now my knowledge management system of choice, and every day endears me to it more intensely.

It is actually a very simple program, and extremely flexible. This is because it is all based on text files – actually Markdown files. So, it’s super portable, and it’s very easy to work with the basic data with tools outside of Obsidian. It meets every criteria on the list above, though the mobile app is still in development. And, like any app still in beta release, one doesn’t know exactly where the line of development will lead.

The bulk of the app is just an editor, some files, and folders. Depending on the actual knowledge management method you decide to use (tags or no tags, folders or no folders, chronological or alphabetical, or…) it can be organized to suit the situation. In this way, you can easily use Obsidian to replicate the basic “file folder” mentality that is represented by the apps already discussed, if you like. But, I’d suggest going beyond if you want to study Chinese medicine using this app.

Remember that I was looking for an app that encourages interconnection among pieces of information.

I mentioned that TheBrain allows for interconnection – you can create links between one “thought” (mindmap node) and another in an endless combination, as well as using tags and categories to link otherwise isolated ideas. But, this is an active process. One has to know the interconnections and implement the process to make those interconnections visual within the mindmap. This situation doesn’t help me find interconnections, or generate new knowledge.

This is where this article could quickly go off the rails into a 4000 word expounding on an entirely new concept to most of you – Zettelkasten. This is a knowledge management method developed by a sociologist which makes finding new connections not just possible, but inevitable. At root, the system just asks you to put one idea on a notecard (digital or otherwise) and when adding a new idea, force yourself to look at existing ideas to determine the new note’s relationship to what’s there. For now, I’ll stop with that simple explanation. Obsidian is the perfect app to help engage this method of knowledge management, and that’s what I’m implementing now.

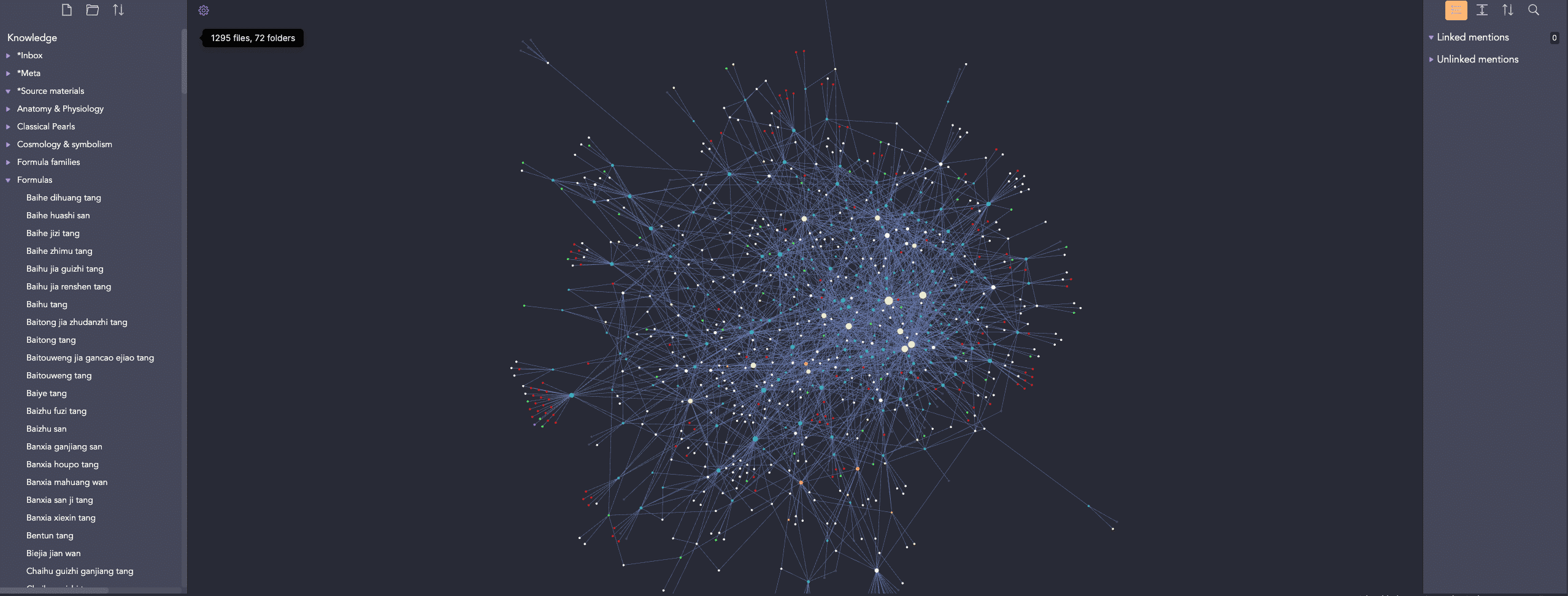

I’ll write some more posts about this app and how I’m using it in the future. You can explore the links in the article so far to see what others have said about it. But, I want to give you a brief glimpse into a database I’m building. I’m showing you a special view of the database that displays a chronological unfolding of what’s in my database so far. Obsidian calls this the “graph view,” and the chronological feature is a new one that I’m finding to be very entertaining!

It has an almost organic feeling to it, I think. Like cells dividing, combining, differentiating.

Note that this is a tiny fraction of the information that this graph will eventually represent. I will share future iterations so you can see the growth and development. From looking at others’ databases, I know that what will happen is that more large clusters of links will emerge. It is partly in exploring these clusters and what they represent that makes this knowledge management system so powerful.

As you watch the video, know that each dot/circle represents a single note – a text file – with information in it. The lines represent the links between notes. More links to a note mean more density in the mindmap. And as more notes are added and connected, the whole orientation of the map shifts. In my next article, I’ll show you some more specifics about how the system works for me.

You can view the video by clicking this link. Worth your time!

[…] to your mind when you consider your situation. You can do it in a list format, on a whiteboard, using a mindmap, or even by audio while you’re out walking with your headphones on. The goal isn’t to […]